30 September 2010

29 September 2010

27 September 2010

CLTV: Should the Government Give Defendants Vouchers Instead of a Court Appointed Attorney?

If you want a copy of this paper for yourself contact CATO at (202) 842-0200 or through the website www.cato.org.

Video quality not quite as high this week because it was going to take over 20 hours to upload. Consequently, I compressed it as a .mov and only had to spend an hour uploading it. And, yes, I know that I goofed at the end and didn't shrink the logo up into the corner, but ya'll had already seen enough of my ugly mug by then anyway. ;-)

23 September 2010

20 September 2010

Anchoring Pleas & Judicial Negotiation

A reply to Professor Miller's article on the participation of judges in plea negotiations.

If you want to read the article yourself you can find it here.

17 September 2010

16 September 2010

13 September 2010

CLTV: Inferring Malice

Restarting the weekly CLTV. There are some glitches this week in the intro and the text at the end. As well, the points made could be tighter. It could probably all have been fixed, but I was getting over some sort of illness yesterday and just didn't have the strength to keep fighting it. :-P

From CLTV.

From CLTV.

11 September 2010

Off Point: The Ole Miss Admiral Akhbars

"If Admiral Akhbar was truly adopted, the average student's IQ at the University of Mississippi would sky rocket."

09 September 2010

08 September 2010

Court in Kentucky (compared to Virginia)

Being a curious sort, I was in Kentucky today and arranged to sit in and watch a general district court in session. It was interesting to see how the practices compared with the Virginia general district court.

Much like Virginia, the general district court in Kentucky is a court for misdemeanors and preliminary hearings on felonies. The courts have different "departments" each of which has its own judge. If something is in Department 1 the case is Judge Smith's. If something is in Department 2 the case is Judge Jones'. I guess this is done primarily as a means of docket control. We don't do this in Virginia. If there are three judges in a county the case just gets put on Judge Smith's docket or Judge Jones' docket, without any further indicators. Unlike Virginia, jury trials are held in district court. There is a right of appeal to the circuit court, but I am uncertain what that entails. In Virginia a defendant cannot get a court of record or a misdemeanor jury trial unless he appeals a conviction in general district court. I don't think that a Kentucky defendant can get two bites at the jury apple, but I don't know the nuts and bolts of a misdemeanor appeal.

When court started, the first thing the judge did was read the assembled defendants their rights. This included their Miranda rights and their rights under Kentucky law. We don't do that in Virginia. An interesting right in Kentucky is that preliminary hearings must take place within ten days if the defendant is incarcerated and twenty if he is on the street. There's nothing like that in Virginia; we'll do the preliminary hearing when we do the preliminary hearing (generally within a couple months).

The docket was organized so that every case had a "call" number. While cases weren't necessarily called in order, each case was referred to by its call number: "Call number 6, Commonwealth v. Smith." Nothing like that in Virginia; we just list the defendants alphabetically.

Part of the day was spent on the first appearance of several defendants in court. The defendant would get called up, the judge would ask the prosecutor if there was an offer and the prosecutor would either make an offer which the defendant could accept on the spot or say "no offer." If the defendant refused the deal or the prosecutor said "no offer" the case was set over to a later date for trial. This is very different from Virginia. We don't usually have a prosecutor participate in the first appearance. All the Virginia judge does is tell the defendant his charges, determine what the defendant will do about an attorney, and address bond. Kentucky also has its judges arraign the defendant at the first appearance. Virginia doesn't do this (more accurately, some Virginia judges do, but it has absolutely no legal affect). I must say, seeing the judge and prosecutor interact with a defendant without even addressing whether the defendant wanted an attorney was the thing which most shocked me as a Virginia attorney. However, the judge has already informed everyone of their rights by then, so they know they have a right to an attorney, and it is the citizen's duty to assert his rights. I can see how it passes muster. It was just so very foreign to my experience

Much like misdemeanor cases everywhere, most cases were settled with "pretrial diversion", time served, "conditionally discharged" time, or a fine. "Pretrial diversion" appeared to be what Virginia calls "taking the case under advisement": go forth and sin no more and in 6-12 months we will make your charge disappear (if you've not gotten in any other trouble). "Conditionally discharged" time seemed to be what Virginia calls suspended time: you're convicted, but you won't have to serve this time unless you get into trouble again in the next year or two.

While procedure and substantive crimes had a lot of similarities, the language was often quite different - although usually I could suss out the meaning thru context. In addition to the different names already listed above, I heard things like "court trial" (bench trial), "cold checks" (bad checks), "3d degree trafficking" (distribution schedule IV or V), failure to appear - warrant of arrest (capias), etc. My favorite of all these was "criminal mischief", which I pictured in my mind as somebody getting drunk, putting on a clown suit, and sneaking around giving people hot foots. It turns out it was just what we in Virginia rather banally call destruction of property; personally, I prefer the imagery that criminal mischief implies.

Finally, Kentucky has a charge which we need in Virginia: "prescription not in proper container." This appears to be a charge for not keeping the pills in the container in which they came from the pharmacy. For those of you in areas where the prescription drug abuse problem hasn't been noticed yet, requiring people to keep the pills in the container that states when they were obtained and how many were obtained is extremely useful (as opposed to the mixed bag of random pills under the driver's seat which he miraculously comes up with a scrip for each and every type of pill once charged).

Much like Virginia, the general district court in Kentucky is a court for misdemeanors and preliminary hearings on felonies. The courts have different "departments" each of which has its own judge. If something is in Department 1 the case is Judge Smith's. If something is in Department 2 the case is Judge Jones'. I guess this is done primarily as a means of docket control. We don't do this in Virginia. If there are three judges in a county the case just gets put on Judge Smith's docket or Judge Jones' docket, without any further indicators. Unlike Virginia, jury trials are held in district court. There is a right of appeal to the circuit court, but I am uncertain what that entails. In Virginia a defendant cannot get a court of record or a misdemeanor jury trial unless he appeals a conviction in general district court. I don't think that a Kentucky defendant can get two bites at the jury apple, but I don't know the nuts and bolts of a misdemeanor appeal.

When court started, the first thing the judge did was read the assembled defendants their rights. This included their Miranda rights and their rights under Kentucky law. We don't do that in Virginia. An interesting right in Kentucky is that preliminary hearings must take place within ten days if the defendant is incarcerated and twenty if he is on the street. There's nothing like that in Virginia; we'll do the preliminary hearing when we do the preliminary hearing (generally within a couple months).

The docket was organized so that every case had a "call" number. While cases weren't necessarily called in order, each case was referred to by its call number: "Call number 6, Commonwealth v. Smith." Nothing like that in Virginia; we just list the defendants alphabetically.

Part of the day was spent on the first appearance of several defendants in court. The defendant would get called up, the judge would ask the prosecutor if there was an offer and the prosecutor would either make an offer which the defendant could accept on the spot or say "no offer." If the defendant refused the deal or the prosecutor said "no offer" the case was set over to a later date for trial. This is very different from Virginia. We don't usually have a prosecutor participate in the first appearance. All the Virginia judge does is tell the defendant his charges, determine what the defendant will do about an attorney, and address bond. Kentucky also has its judges arraign the defendant at the first appearance. Virginia doesn't do this (more accurately, some Virginia judges do, but it has absolutely no legal affect). I must say, seeing the judge and prosecutor interact with a defendant without even addressing whether the defendant wanted an attorney was the thing which most shocked me as a Virginia attorney. However, the judge has already informed everyone of their rights by then, so they know they have a right to an attorney, and it is the citizen's duty to assert his rights. I can see how it passes muster. It was just so very foreign to my experience

Much like misdemeanor cases everywhere, most cases were settled with "pretrial diversion", time served, "conditionally discharged" time, or a fine. "Pretrial diversion" appeared to be what Virginia calls "taking the case under advisement": go forth and sin no more and in 6-12 months we will make your charge disappear (if you've not gotten in any other trouble). "Conditionally discharged" time seemed to be what Virginia calls suspended time: you're convicted, but you won't have to serve this time unless you get into trouble again in the next year or two.

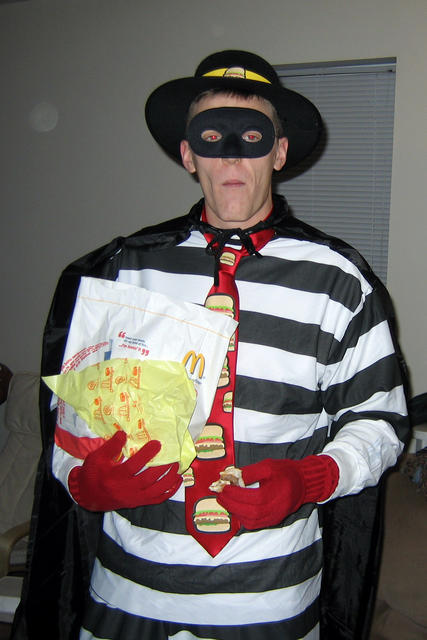

While procedure and substantive crimes had a lot of similarities, the language was often quite different - although usually I could suss out the meaning thru context. In addition to the different names already listed above, I heard things like "court trial" (bench trial), "cold checks" (bad checks), "3d degree trafficking" (distribution schedule IV or V), failure to appear - warrant of arrest (capias), etc. My favorite of all these was "criminal mischief", which I pictured in my mind as somebody getting drunk, putting on a clown suit, and sneaking around giving people hot foots. It turns out it was just what we in Virginia rather banally call destruction of property; personally, I prefer the imagery that criminal mischief implies.

Finally, Kentucky has a charge which we need in Virginia: "prescription not in proper container." This appears to be a charge for not keeping the pills in the container in which they came from the pharmacy. For those of you in areas where the prescription drug abuse problem hasn't been noticed yet, requiring people to keep the pills in the container that states when they were obtained and how many were obtained is extremely useful (as opposed to the mixed bag of random pills under the driver's seat which he miraculously comes up with a scrip for each and every type of pill once charged).

02 September 2010

01 September 2010

30 August 2010

The Right to Arm for Self Defense

So, you have the right to bear arms and you have the right to defend yourself, but what if you arm yourself in anticipation of defending yourself?

In Virginia, the answer is that if you have armed yourself in reaction to a threat the inference of malice that the use of a firearm in a homicide carries is negated. The same rule probably carries for lesser offenses such as malicious wounding, but the cases which set the rule are homicide cases. Generally, this has been laid out in a series of decisions having to do with jury instructions. The best statement of this probably comes from Bevley v. Commonwealth, JUN46, VaSC No. 3097:

This right to arm extends so far that in Jones v. Commonwealth, JAN48, Va. No. 3304 a man who was clearly threatened could go home, arm himself, and wait on his porch for the man who threatened him to come was entitled to the right to arm instruction.

There are some limitations to the requirement that the instruction be given. Reasoning that the right to arm instruction is based upon a need to counter the available inference that if someone purposefully arms himself the act of doing so indicates malicious intent, the Virginia Court of Appeals has stated the instruction is not appropriate when the defendant merely grabbed an available weapon to defend himself or his family. Lynn v. Commonwealth, MAY98, VaApp No. 0109-97-3. I take this to mean that since the defendant didn't purposefully seek a weapon there is nothing to counteract from the purposeful seeking of the weapon and therefore, the only instruction needed is the self defense instruction - not the right to arm instruction.

So, what exactly is the instruction? Well, here's the one from Bevley:

It's an interesting line of reasoning and carries all sorts of questions. Does the threat have to be individualized? Can a Blood carry a sidearm because he knows that the Latin Kings are trying to kill Bloods in the City? The cases refer to the right to arm. How does this right play out with felons or others who are forbidden by mere laws from possessing firearms? Can a felon carry a firearm if he knows that the Pagans are hunting him? Personally, I think there has to be an individualized threat which has some immediacy.

In Virginia, the answer is that if you have armed yourself in reaction to a threat the inference of malice that the use of a firearm in a homicide carries is negated. The same rule probably carries for lesser offenses such as malicious wounding, but the cases which set the rule are homicide cases. Generally, this has been laid out in a series of decisions having to do with jury instructions. The best statement of this probably comes from Bevley v. Commonwealth, JUN46, VaSC No. 3097:

It is a fundamental doctrine that a person who has been threatened with death or serious bodily harm and has reasonable grounds to believe that such threats will be carried into execution, has the right to arm himself in order to combat such an emergency. Whether the threats were made, or the accused had reason to believe they would be carried into execution, were questions to be determined by the jury. However, when a jury is told that the law presumes that a person using a deadly weapon to kill another acts with malice and throws upon the accused the burden of disproving malice, then the accused is entitled as a matter of law to have the jury instructed that he has overcome the presumption, if they believe the evidence offered in his behalf.Of course, this uses the old "presume" language, which we have scrapped nowadays in favor of telling juries that they can infer. Nevertheless, the principal in the decision is still sound.

This right to arm extends so far that in Jones v. Commonwealth, JAN48, Va. No. 3304 a man who was clearly threatened could go home, arm himself, and wait on his porch for the man who threatened him to come was entitled to the right to arm instruction.

There are some limitations to the requirement that the instruction be given. Reasoning that the right to arm instruction is based upon a need to counter the available inference that if someone purposefully arms himself the act of doing so indicates malicious intent, the Virginia Court of Appeals has stated the instruction is not appropriate when the defendant merely grabbed an available weapon to defend himself or his family. Lynn v. Commonwealth, MAY98, VaApp No. 0109-97-3. I take this to mean that since the defendant didn't purposefully seek a weapon there is nothing to counteract from the purposeful seeking of the weapon and therefore, the only instruction needed is the self defense instruction - not the right to arm instruction.

So, what exactly is the instruction? Well, here's the one from Bevley:

The court further tells the jury that when a person reasonably apprehends that another intends to attack him for the purpose of killing him or doing him serious bodily harm, then such person has a right to arm himself for his own necessary self-defense."And here's the one that was rejected as unnecessary in Lynn:

When a person reasonably apprehends that another intends to attack him or a member of his family for the purpose of killing him or a member of his family or doing him or a member of his family serious bodily harm, then such person had a right to arm himself for his own necessary self-protection and the protection of his family, and in such case, no inference of malice can be drawn from the fact that he prepared for it.The second covers all the bases, so I think it's the better of the two.

It's an interesting line of reasoning and carries all sorts of questions. Does the threat have to be individualized? Can a Blood carry a sidearm because he knows that the Latin Kings are trying to kill Bloods in the City? The cases refer to the right to arm. How does this right play out with felons or others who are forbidden by mere laws from possessing firearms? Can a felon carry a firearm if he knows that the Pagans are hunting him? Personally, I think there has to be an individualized threat which has some immediacy.

26 August 2010

25 August 2010

Introducing the Rejected Plea Agreement

Probative/Prejudicial

Even if it gets past both hearsay and relevance objections, the proposed introduction of the rejected plea offer must have its probative value balanced against its possible prejudicial and misleading effect upon the fact finder. The two possible matters for which the rejected plea agreement could be offered are for proof of the prosecution's perception that its case has weaknesses and “the mere existence of a favorable plea offer is some evidence of an innocent state of mind by the defendant.”

The actual strength or weakness of the case will play itself out in front of the finder of fact. The prosecutor's perception of the case's strength does not change the strength of the evidence presented. Introducing the rejected plea agreement for the purpose of showing that the prosecutor thought the case was weak is asking the fact finder to substitute the prosecutor's judgment for his/their own. The prosecutor's perception adds nothing to the actual evidence and has a substantial risk of prejudicing or misleading the fact finder by inviting him/them to adopt the prosecutor's perception rather than coming to a conclusion based solely upon the facts.

The rejection of the plea offer as proof of the defendant's innocent state of mind is problematic. Anyone who has done defense work has seen defendants turn down all sorts of favorable deals for reasons other than innocence. Among the more unusual ones I ran across were the beliefs that mispelling a name on an indictment meant the prosecution could not convict and an abiding belief that the UCC denied the Commonwealth of Virginia the ability to prosecute for criminal failure to pay child support. More common are defendants who don't believe certain witnesses will testify against them; defendants who don't want to do any time (they will turn down 6 months despite being told they will get 2 years if they go to trial); defendants refusing the plea offer today because it would require them to go to jail today (in effect buying an extra couple months on the street with years in prison; defendants who feel like any conviction will destroy their lives/jobs; &cetera. Often, the choice to reject the plea offer and go to trial is irrational. Professor Miller even acknowledges this phenomenon:

Under both possible uses of the rejected plea agreement the potential toward prejudice and misleading the finder of facts is greater than any actual evidence putatively to be found in the offer.

The actual strength or weakness of the case will play itself out in front of the finder of fact. The prosecutor's perception of the case's strength does not change the strength of the evidence presented. Introducing the rejected plea agreement for the purpose of showing that the prosecutor thought the case was weak is asking the fact finder to substitute the prosecutor's judgment for his/their own. The prosecutor's perception adds nothing to the actual evidence and has a substantial risk of prejudicing or misleading the fact finder by inviting him/them to adopt the prosecutor's perception rather than coming to a conclusion based solely upon the facts.

The rejection of the plea offer as proof of the defendant's innocent state of mind is problematic. Anyone who has done defense work has seen defendants turn down all sorts of favorable deals for reasons other than innocence. Among the more unusual ones I ran across were the beliefs that mispelling a name on an indictment meant the prosecution could not convict and an abiding belief that the UCC denied the Commonwealth of Virginia the ability to prosecute for criminal failure to pay child support. More common are defendants who don't believe certain witnesses will testify against them; defendants who don't want to do any time (they will turn down 6 months despite being told they will get 2 years if they go to trial); defendants refusing the plea offer today because it would require them to go to jail today (in effect buying an extra couple months on the street with years in prison; defendants who feel like any conviction will destroy their lives/jobs; &cetera. Often, the choice to reject the plea offer and go to trial is irrational. Professor Miller even acknowledges this phenomenon:

It is well established that guilty defendants as a class are unusually prone to risk taking because, inter alia, a criminal history suggests a preference for gambling, just as it suggests that the defendant fears punishment less than most people. Conversely, risk aversion is a much more plausible assumption where innocent defendants are concerned (especially those with relatively clean records). Therefore, critics…claim that plea bargaining coerces a significant percentage of innocent defendants to convict themselves in exchange for a certain, reduced penalty.With all this in mind, there is no basis for stating that rejecting a plea offer is indicative of either a belief in innocence or actual innocence. In fact, per Professor Miller's statement supra it appears that rejecting a plea agreement actually tends to show guilt more than innocence. With that in mind, offering the rejected plea offer as proof of the defendant's innocence has a strong potential to mislead the finder of fact.

Under both possible uses of the rejected plea agreement the potential toward prejudice and misleading the finder of facts is greater than any actual evidence putatively to be found in the offer.

24 August 2010

Introducing the Rejected Plea Agreement

Hearsay & Relevance

Professor Miller addresses the hearsay problem and makes a case for allowing the introduction of the plea agreement under an exception as indicative of the state of mind of the prosecutor.

My experience, and I daresay that most prosecutors would back me up on this, is that weakness of a case almost never comes from the thought that the defendant might be innocent. Most of the cases in which there is a question on my office's part are flushed out before I get assigned to prosecute the felony. In my case the primary cause for concern that the case is weak is a worry that I will not be able to get witnesses to court. The clerk who was robbed while working the late shift no longer works at the eZee Stop. The Officer who took the confession no longer works in the police department. The co-defendant who identifies the defendant is serving time in another State which may not want to send him back to be a witness. There are also plenty of other reasons for concern over a case. Admissibility of evidence may be a concern, particularly when there is a shift in constitutional precedent such as after Arizona v. Gant. There may be a concern that witnesses (momma, mamaw) may refuse to testify or develop memory loss because they don't want “little Bobby” to go to jail. Every honest prosecutor will tell you he's lost track of the number of times he's gotten a file in his hands which leaves him no doubt as to whether the defendant is guilty but boatloads of doubt as to whether he can prove that guilt.

Why is all this important? Because, a statement that a prosecutor believes a defendant is quite possibly innocent is a statement countering the prosecution's assertion at trial that the defendant is guilty. However, a statement that the case is weak is a statement of the difficulty of putting the case together, not a comment on innocence. Therefore, the offered plea, as merely a comment on the difficulty of putting the case together, should not be admitted as an exception to the hearsay rule.

--------------------------------------------------

Even assuming the evidence makes it past the hearsay exception, it must pass the basic test that all evidence must: is it relevant? As the plea offer is about the weakness of the prosecutor's case and not about the innocence of the defendant it is not. The difficulty which the prosecutor went through in getting his evidence together (or failing to get certain parts) is not a concern of the fact finder. The fact finder is to review the evidence in front of him/them and make a decision based upon that evidence. The fact that a prosecutor had difficulty putting the case together has no bearing on that decision. The fact that a prosecutor was unable to present some piece of evidence he would have liked to present is only relevant insomuch as it may leave a vital element of the crime unproven and that will play itself out in the trial without the introduction of the rejected plea agreement.

Continued in Wednesday 2 p.m. post.

“In light of this data, evidence of a favorable plea offer by a prosecutor has significant probative value for establishing the weakness of the prosecution's case. While other factors may play a role in a prosecutor offering a favorable plea bargain to a defendant, the above data reveal that nearly every prosecutor is influenced by the weakness of the prosecution's case in making a plea offer. And, “if we assume that prosecutors are motivated by a desire to avoid acquittals, they are likely to adjust their plea offers so as to create the largest differentials in cases where the government evidence is weakest.” Put another way, “the more likely it is that a defendant will be acquitted, the more attractive the plea offer that he will receive.”The flaw in this is that it conflates weakness of the case with innocence. If the favorability of the plea agreement tracked with the prosecutor's belief in the probability of the defendant's innocence - the better the plea offer the stronger the prosecutor's belief that the defendant could be innocent – then a favorable plea offer would clearly be a statement contrary to the Commonwealth's assertion of guilt and should be an exception to the hearsay rule. If Brady and its progeny are stretched a little they could require the admission of a prosecutor's admission that a defendant might be innocent. However, weakness of a case rarely has to do with a prosecutor's belief that the defendant is innocent.

My experience, and I daresay that most prosecutors would back me up on this, is that weakness of a case almost never comes from the thought that the defendant might be innocent. Most of the cases in which there is a question on my office's part are flushed out before I get assigned to prosecute the felony. In my case the primary cause for concern that the case is weak is a worry that I will not be able to get witnesses to court. The clerk who was robbed while working the late shift no longer works at the eZee Stop. The Officer who took the confession no longer works in the police department. The co-defendant who identifies the defendant is serving time in another State which may not want to send him back to be a witness. There are also plenty of other reasons for concern over a case. Admissibility of evidence may be a concern, particularly when there is a shift in constitutional precedent such as after Arizona v. Gant. There may be a concern that witnesses (momma, mamaw) may refuse to testify or develop memory loss because they don't want “little Bobby” to go to jail. Every honest prosecutor will tell you he's lost track of the number of times he's gotten a file in his hands which leaves him no doubt as to whether the defendant is guilty but boatloads of doubt as to whether he can prove that guilt.

Why is all this important? Because, a statement that a prosecutor believes a defendant is quite possibly innocent is a statement countering the prosecution's assertion at trial that the defendant is guilty. However, a statement that the case is weak is a statement of the difficulty of putting the case together, not a comment on innocence. Therefore, the offered plea, as merely a comment on the difficulty of putting the case together, should not be admitted as an exception to the hearsay rule.

--------------------------------------------------

Even assuming the evidence makes it past the hearsay exception, it must pass the basic test that all evidence must: is it relevant? As the plea offer is about the weakness of the prosecutor's case and not about the innocence of the defendant it is not. The difficulty which the prosecutor went through in getting his evidence together (or failing to get certain parts) is not a concern of the fact finder. The fact finder is to review the evidence in front of him/them and make a decision based upon that evidence. The fact that a prosecutor had difficulty putting the case together has no bearing on that decision. The fact that a prosecutor was unable to present some piece of evidence he would have liked to present is only relevant insomuch as it may leave a vital element of the crime unproven and that will play itself out in the trial without the introduction of the rejected plea agreement.

Continued in Wednesday 2 p.m. post.

23 August 2010

Introducing a Rejected Plea Offer into Evidence

Perceptual Evidence

Colin Miller, of EvidenceProf Blog fame, sent me a link to an article he's written espousing the virtues of allowing a rejected plea agreement to be introduced by the defendant as evidence tending to prove innocence. It's an interesting article, but I must disagree with its conclusion.

The introduction of a plea offer is something which might best be called perceptual evidence. It wouldn't prove or disprove a physical element of a charged crime. Instead, it is meant to change how the finder of fact perceives the evidence. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Perceptual evidence is used in court in almost every trial. Most often we see this when evidence is introduced to show a witness' bias or when the prior convictions of a witness are introduced to show a lack of moral reliability. A less common example is one that Professor Miller offers: the introduction of the fact that a defendant refused immunity offered by the prosecution. None of these are actually a piece of positive evidence proving or disproving a physical element of the charged crime.

Perceptual evidence is per force a tricky area. It is the introduction of bias into the trial. In fact, the examples above all play toward a bias which has been approved by our jurisprudence. We conclude that a person who has been given a benefit from the prosecution in exchange for his testimony is, to some extent, likely to fabricate testimony against the defendant. We conclude that someone who has been convicted of a felony or misdemeanor involving “moral turpitude” is more likely to lie during his testimony. Courts have concluded that the fact that a defendant turned down an offer of immunity is indicative of a belief that he is innocent. All of these are officially sanctioned biases which are introduced to influence the perception of other evidence which has been introduced.

On the other hand, there is plenty of perceptual evidence which is out of bounds. Of course, blatant plays toward prejudices involving race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, &cetera are off limits. However, there are also any number of evidential items which are off limits due to judicial precedent. Neither the prosecution nor the defense can introduce the results of a polygraph test. The prosecution cannot introduce the defendants 10 prior convictions for the same type of offense; under Virginia law the prosecutor could ask a defendant who has chosen to testify how many felonies and moral turpitude misdemeanors he has been convicted of, but no questions beyond the number are allowed.

So, how do we determine if a defendant should be allowed to introduce the perceptual evidence of a rejected plea offer to the finder of fact during a trial? Personally, I see three obstacles. The first is that the plea offer is hearsay. The second is whether the plea offer is relevant. The third is the probative/prejudicial test.

Continued in Tuesday 2 p.m. post.

The introduction of a plea offer is something which might best be called perceptual evidence. It wouldn't prove or disprove a physical element of a charged crime. Instead, it is meant to change how the finder of fact perceives the evidence. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Perceptual evidence is used in court in almost every trial. Most often we see this when evidence is introduced to show a witness' bias or when the prior convictions of a witness are introduced to show a lack of moral reliability. A less common example is one that Professor Miller offers: the introduction of the fact that a defendant refused immunity offered by the prosecution. None of these are actually a piece of positive evidence proving or disproving a physical element of the charged crime.

Perceptual evidence is per force a tricky area. It is the introduction of bias into the trial. In fact, the examples above all play toward a bias which has been approved by our jurisprudence. We conclude that a person who has been given a benefit from the prosecution in exchange for his testimony is, to some extent, likely to fabricate testimony against the defendant. We conclude that someone who has been convicted of a felony or misdemeanor involving “moral turpitude” is more likely to lie during his testimony. Courts have concluded that the fact that a defendant turned down an offer of immunity is indicative of a belief that he is innocent. All of these are officially sanctioned biases which are introduced to influence the perception of other evidence which has been introduced.

On the other hand, there is plenty of perceptual evidence which is out of bounds. Of course, blatant plays toward prejudices involving race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, &cetera are off limits. However, there are also any number of evidential items which are off limits due to judicial precedent. Neither the prosecution nor the defense can introduce the results of a polygraph test. The prosecution cannot introduce the defendants 10 prior convictions for the same type of offense; under Virginia law the prosecutor could ask a defendant who has chosen to testify how many felonies and moral turpitude misdemeanors he has been convicted of, but no questions beyond the number are allowed.

So, how do we determine if a defendant should be allowed to introduce the perceptual evidence of a rejected plea offer to the finder of fact during a trial? Personally, I see three obstacles. The first is that the plea offer is hearsay. The second is whether the plea offer is relevant. The third is the probative/prejudicial test.

Continued in Tuesday 2 p.m. post.

Introducing the Rejected Plea Agreement into Evidence

Colin Miller, of EvidenceProf Blog fame, sent me a link to an article he's written espousing the virtues of allowing a rejected plea agreement to be introduced by the defendant as evidence tending to prove innocence.

I have penned a three part reply which shall post at 2 p.m. Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday:

Monday - Introducing a Rejected Plea Offer into Evidence: Perceptual Evidence

Tuesday - Introducing the Rejected Plea Agreement: Hearsay & Relevance

Wednesday - Introducing the Rejected Plea Agreement: Probative/Prejudicial

I have penned a three part reply which shall post at 2 p.m. Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday:

Monday - Introducing a Rejected Plea Offer into Evidence: Perceptual Evidence

Tuesday - Introducing the Rejected Plea Agreement: Hearsay & Relevance

Wednesday - Introducing the Rejected Plea Agreement: Probative/Prejudicial

19 August 2010

Winner of Last Week's Name That Pic

And they say exercising makes you live longer. What a croc.

This week's selection brought to you by Scruffy.

This week's selection brought to you by Scruffy.

McNuggets Rage

Apparently, this is a woman in Ohio who really wanted her McNuggets and was denied their ineffable heavenliness.

17 August 2010

Come up with a new excuse

There's a persistent problem with groups of Yahoos getting in a truck and driving up to a mine/train station/garage and grabbing wire/metal brakes/engines and going down to the friendly local scrap metal dealer and turning it into cash.

Here are a tip for those of you defending one of these Yahoos when I've been assigned to prosecute the case:

Please tell him that unless the stuff was picked up during business hours, while workers were on site, I am not going to believe that his buddy told him that Buddy had permission to take that $8,000 air pump meant to keep people alive in the mine and go to the scrap yard to get $500 for it. Even if Buddy said such a thing, I don't believe anyone is stupid enough to think that it was kosher when they took it at 5 a.m. using flashlights.

It's the same excuse every single time. Tell them to come up with something more creative. It probably won't help much, but at least a claim that space aliens made him do it would keep the rest of us entertained.

Here are a tip for those of you defending one of these Yahoos when I've been assigned to prosecute the case:

Please tell him that unless the stuff was picked up during business hours, while workers were on site, I am not going to believe that his buddy told him that Buddy had permission to take that $8,000 air pump meant to keep people alive in the mine and go to the scrap yard to get $500 for it. Even if Buddy said such a thing, I don't believe anyone is stupid enough to think that it was kosher when they took it at 5 a.m. using flashlights.

It's the same excuse every single time. Tell them to come up with something more creative. It probably won't help much, but at least a claim that space aliens made him do it would keep the rest of us entertained.

Thanx to Mark Draughn

For those of you who are now viewing this blawg correctly, you can thank Mark, who figured out what was wrong with it in about ten seconds flat. It turns out, if you don't tell Explorer that you want your website to run the way you wrote then Explorer will go into a mode that will make sure your website doesn't run properly. Whodathunkit?

CLTV in Better Def:

Virginia Appellate Decisions July 2010

It's in better def than yesterdays and it doesn't cut anything off. I'm not sure why it shrinks into the black box. I'll try to fix that next time.

16 August 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)